Manila is striving to bolster its military amid increased Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea.

China continues to use dangerous tactics against the Philippines in the South China Sea, as demonstrated by incidents in August in which the China Coast Guard (CCG) rammed Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) vessels and the People’s Liberation Army Air Force fired flares at Philippine aircraft. The Biden administration has repeatedly said that any attack on Philippine ships or aircraft would bring the US-Philippine Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) into play.

Subsidiary Impacts

- It could take up to ten years for new arms purchases to be delivered and fully integrated into the country’s military.

- China will refrain from occupying and building artificial islands on Philippine-claimed atolls.

- US Navy ships will not escort rotation and resupply missions to the Philippine garrison on Second Thomas Shoal.

Analysis

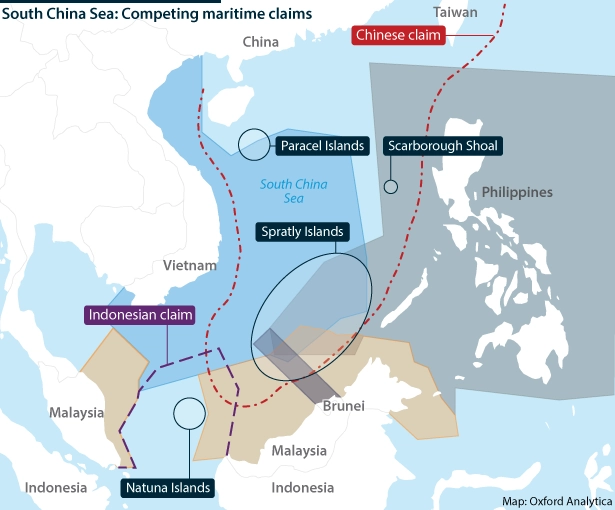

The Philippines and China are among the handful of players with competing claims in the South China Sea.

Since taking office in 2022, President Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos has pushed back hard against Chinese assertiveness in the Philippine exclusive economic zone (EEZ). This contrasts with the approach of his immediate predecessor Rodrigo Duterte, who dismissed maritime tensions with China and downgraded military ties with the United States in an attempt to attract Chinese infrastructure investment (see PHILIPPINES: Diplomatic balancing act gets harder – May 19, 2023).

Marcos has vigorously asserted Manila’s claims to roughly 50 of the features in the Spratly Islands and defended its sovereign rights to living and non-living resources in the Philippine EEZ.

The many confrontations since mid-2023 between Philippine and Chinese vessels in disputed waters have included several encounters linked to Philippine rotation and resupply missions to Second Thomas Shoal, a Philippine-occupied atoll in the Spratlys — within the Philippine EEZ — where Manila has a garrison manning a deliberately grounded warship. Talks between Manila and Beijing have failed to reduce tensions over this feature.

Second Thomas Shoal is a key point of contention

The Marcos administration’s South China Sea policy involves:

- urging China to abide by a 2016 UN-backed arbitral tribunal award which deemed Beijing’s expansive South China Sea claims invalid under international maritime law;

- improving infrastructure on the few features that the Philippines occupies, including the rusting warship at Second Thomas Shoal;

- publicising dangerous moves undertaken by the People’s Liberation Army, the CCG and China’s maritime militia against Philippine vessels and aircraft;

- consolidating the alliance with the United States and defence relationships with other countries by increasing the frequency of training exercises and maritime patrols; and

- accelerating the country’s defence modernisation programme.

Of these five elements, the fourth and fifth are the most consequential.

Defence ties

The 1951 MDT means it would be risky for China to escalate its aggression towards the Philippines.

US-Philippine alliance

Under President Joe Biden, the United States has said on multiple occasions that its defence commitment to the Philippines is “ironclad”. It is unclear whether Donald Trump would give the same assurance if he returned to the White House after this November’s presidential election, but for the time being at least, the Philippines can count on US intervention if attacked.

At the May 31-June 2 Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, Marcos indicated that the killing of a Philippine national in a “wilful” act in the South China Sea would constitute an act of war.

The MDT is crucial to Philippine security

In 2023, Manila and Washington agreed to revise their Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) — which allows US forces to deploy rotationally to the Philippines and store equipment there — to cover nine bases, up from five. Biden’s budget request for fiscal year 2024/25 (October-September) includes sizeable financing to improve facilities at EDCA sites.

Since last November, the Philippine and US militaries have conducted joint sea and air patrols in the Philippine EEZ. They have also undertaken joint patrols involving other militaries.

US-Philippine military exercises have grown in scope, frequency and complexity to replicate real-world combat situations. The latest iteration of the annual Balikatan exercise, held between April and May, involved more than 16,000 military personnel and simulated the recapture of features in the South China Sea.

Despite closer defence relations, the Philippines has refrained from asking the United States to escort Philippine vessels on missions to Second Thomas Shoal, because it wants to be seen as acting in its own interests and not those of Washington.

Defence relationships with other countries

The Marcos administration is pursuing closer defence links with partners besides the United States. It has signed various defence cooperation agreements that principally facilitate military exercises and humanitarian and disaster relief operations but could also be invoked amid a regional security crisis.

The two most important non-US defence partners of the Philippines are Japan and Australia, both of which are US allies.

In 2023, Japan agreed to fund a coastal radar system for the Philippines and five PCG patrol boats under its new Official Security Assistance programme. More significantly, in July this year, the two countries signed a Reciprocal Access Agreement that is similar to the Philippine-US Visiting Forces Agreement and the Philippine-Australian Status of Visiting Forces Agreement.

The Philippines and Australia have stepped up joint military training and exercises. Moreover, in 2021, they finalised an agreement that allows logistical support between their armed forces.

Among its ASEAN partners, the Philippines has prioritised closer security ties with Vietnam, another South China Sea claimant. In January, the two countries signed memorandums of understanding on coast guard cooperation and incident prevention in the South China Sea, leading to the first-ever joint exercise between their coast guards last month.

Military modernisation

A revised Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) Modernisation Act was passed by Congress and approved by then-President Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino in 2012, a few months after China seized Scarborough Shoal. The ensuing modernisation programme slowed during Duterte’s presidency but has gathered momentum under Marcos.

In January, Marcos approved expenditure of PHP2tn (USD35bn) for new defence acquisitions over the next decade.

The priority is the Philippine Navy (PN). Most PN vessels are second-hand warships transferred from the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom and South Korea. The force is eyeing new frigates and submarines.

In 2014, Manila ordered twelve South Korean-made FA-50 Golden Eagle fighter aircraft for the Philippine Air Force (PAF), all of which were delivered by 2017. It may buy another twelve. However, the PAF would like to acquire faster and more lethal jets and is considering the US-made F-16 Fighting Falcon or the Swedish-made JAS-39 Gripen.

In 2022, a few months before Marcos came to power, Manila signed a USD375mn deal with India for three batteries of coastal-based, anti-ship BrahMos supersonic cruise missiles for the Philippine Marine Corps. The first batch arrived in April this year and will enable the AFP to target hostile warships in the Philippine EEZ. The Philippine Army is also considering acquiring BrahMos missiles.

The Marcos government’s procurement plans depend greatly on robust economic growth (see PHILIPPINES: Economy should perform solidly this year – June 27, 2024).

Authored by:

Dr Joydeep Sen

Deputy Director & Senior Analyst,

Asia Pacific

What next?

The Philippines will keep strengthening its defence ties with the United States and other partners to counter Chinese aggression. China will not be deterred from asserting its claims, but it is unlikely to escalate its ‘grey zone’ tactics to use of lethal military force. Increased funding will allow Manila to order new defence equipment including submarines, fighter jets and medium-range missiles.